In the Dynamics Research Group, our research interests span all things structural dynamics. These pages are about our work in developing physics-informed machine learning to enhance our ability to model and make predictions about vibrating structures. The aim here is to bring together the flexibility and power of state-of-the-art machine learning techniques with more structured and insightful physics-based models that can be derived from domain expertise. This page gives an overview of our work through a structural health monitoring example (if you like you can read a more formal version of it here).

Structural health monitoring (SHM) is about using sensors, data and algorithms to detect and predict damage before it causes problems. In the DRG we generally focus on developing algorithms/models to infer the health state of a structure, often achieved through the use of machine learning tools. The potential benefits are vast, not just in terms of increasing safety, but also in terms of the possibility of informed maintenance scheduling (cheaper and greener) and automated decision making.

Why physics-informed ML?

There are lots of reasons why we think combining physics-based and data-driven learners is a good idea. Foremost, we know a lot about how things work - but not everything, physics-informed ML gives us the opportunity to develop models that are informed by our physical insights and from evidence in data. We think that doing this is a natural way to enhance the interpretability of our models and predictions. Importantly, it helps us to overcome some of the barriers of trying to learn from data when you don’t actually have a lot of it (which happens a lot more than you would think…).

When is learning from data not enough? - motivating examples from structural health monitoring

Structures operate in a complex dynamic environment, with environmental and operating conditions regularly varying. Let’s consider, for example, the loading that an aircraft wing is subject to - this will depend upon the exact flight phase that the aircraft is in (e.g. taxiing to the runway, or at cruising altitude), each containing different types of manoeuvres. Ambient temperature and pressure will also be dependent on many factors, such as the local climate and particular altitude. All of these factors will then influence the dynamic behaviour of the wing which we’d ultimately like to be able to model to inform our SHM predictions. To account for these effects, data used to train any predictive model must be representative of the full environmental and operational envelope - this is the nature of a data-driven learner! Unfortunately, in many applications, it is impractical or infeasible to collect data that represents all possible operating conditions. Where models have not been learnt on suitably representative training data, then there is no guarantee that the model will be able to make accurate predictions.

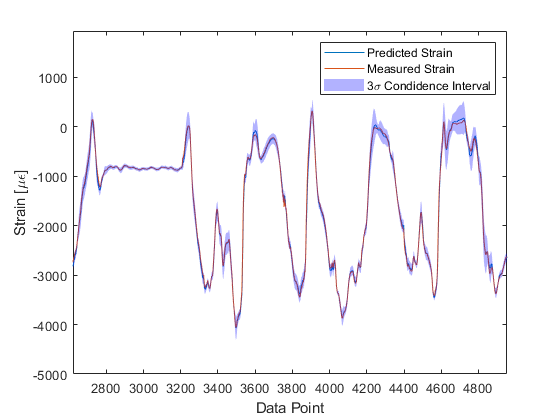

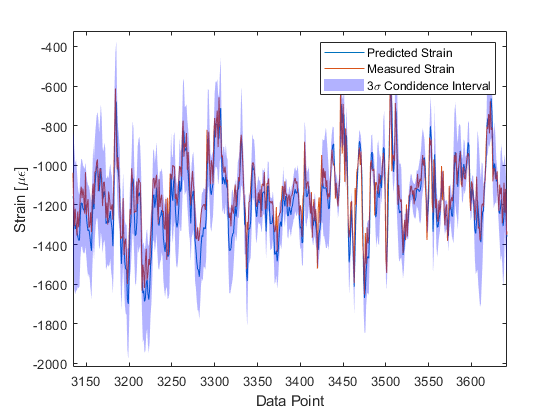

To illustrate this behaviour, let’s take a look at a data-driven model (a Gaussian process) tasked with predicting bending strain on an aircraft wing during different manoeuvres to inform an in-service fatigue assessment. We use data from five different flights to train the model. When testing the model on other flights not included in the training data, most of the time the trained model is able to generalise well and make an accurate prediction of strain. The inset figure shows a prediction of a typical flight, it has very low prediction error for the majority of the time history.

If we move to look at strain predictions made during conditions that were atypical of normal flight behaviour, however, - a low altitude sortie, characterised by a very turbulent response - the model is unable to predict strain as accurately as in the previous instance.

This is because the conditions observed are different to those that were included in the training set (out-of-sample scenarios), with the data-driven model being unable to generalise.

Physics-informed ML for structural dynamics

In an attempt to mitigate some of these problems, a package of work is currently being led within the group by Prof. Lizzy Cross on the use of physics-informed machine learning. The aim here is to bring together the flexibility and power of state-of-the-art machine learning techniques with more structure and insightful physics-based models that can be derived from domain expertise. By combining monitoring data with engineering insight, the objective is to develop models that can learn underlying statistical relationships, but with governing physical principles embedded within the inference.

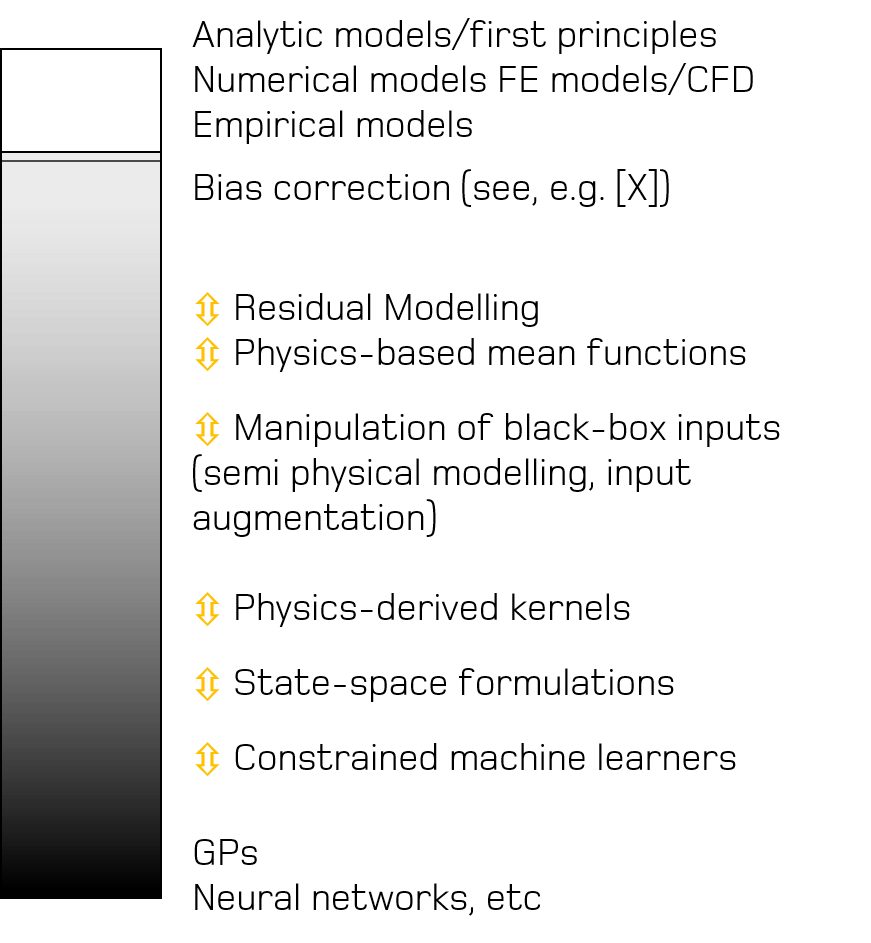

To explore the currently available modelling approaches, we think that it is helpful to consider physics-informed (grey-box) models to be on a spectrum between purely physics-based methods (white-box) and purely data-driven learners (black-box). Publications by the group corresponding to each of these different types of grey-box architecture for structural dynamics are included Here.

At the ``whiter” end of the spectrum are models built from governing physical equations. For example, finite element models , where differential equations that describe the phenomena of interest are numerically solved. Modelling approaches where data are used for model selection and parameter estimation fall nearby. Residual models are those that use a data-driven approach to account for the observed difference between a physical models and observed measurements, with the general form

where f(x) is the output of the physical model, δ(x) is the model discrepancy and ε the noise process. The discrepancy term is often used to correct a miss-specified physical model, giving rise to the term ``bias correction”. In some of our recent work, we have considered residual modelling in the context of compensating for uncaptured/missing behaviours in a physics-based model, which is discussed further in papers under Combining physics-based and machine learning models.

As we progress further along the spectrum of white to black, semi-physical modelling considers the case where features used in a data-driven learner are subject to some transformation before being fed into the model as inputs, and can also be thought of as input augmentation. Examples of grey-box modelling following this architecture can be found under Manipulation of black-box inputs.

When considering kernel-based machine learning methods such as Gaussian processes and support vector machines, a function that defines how similarity between data points should be measured needs to be specified. More formally, this function is defined as the kernel. We can look to encode physical insight into the form of these functions to develop physics-derived kernels, ensuring that the functions drawn from the kernel have physically-relevant structure. Papers related to this topic can be found Here.

At the black end of the spectrum exists constrained machine learners. These methods constrain a machine learner with some physically-derived assumptions or laws that the predictions of the model are guaranteed to satisfy. These types of grey-box models are discussed Here.